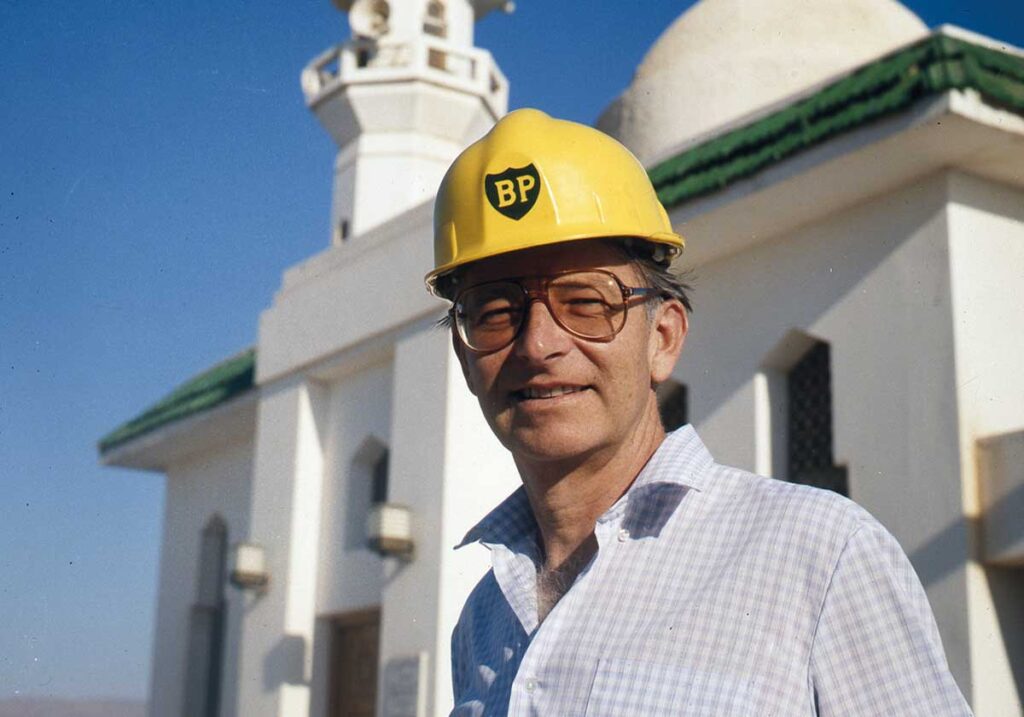

Sir Peter Walters was the chairman of BP from 1981 until 1990. During his tenure he transformed the company into a top-rank international oil company. In chairing the company through almost the entire eighties, Sir Peter proved a special master of the art of managing a large company through a period of stagnant markets and ruthless cost cutting. His mantra was ‘no sacred cows’ as he insisted that each division should either pay its own way or be sold. Following his retirement in 1990 after 35 years with BP, Sir Peter served as chairman for a number of other well-known companies. He died on 11 July 2023, aged 92.

Peter Ingram Walters was born in Birmingham on 11 March 1931. His father, a policeman, was killed in an air raid during the second world war and Peter was brought up by his mother. He won a place at King Edward’s School, Birmingham and gained a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Birmingham in 1952. After national service with the Royal Army Service Corps, Peter joined BP in 1954.

His arrival coincided with a period of continuous growth for the company and his early postings included two in the US where he joined talks with other oil majors and the US government. Between 1965 and 1967 Peter served as vice president of BP North America Inc.

When Peter became managing director in 1973, the time of the first oil shock, BP reacted by diversifying away from oil, moving into coal, minerals and information services. However, on becoming the youngest chairman in the corporation’s history in November 1981 in succession to Sir David Steel, focus replaced diversification. Eventually, IT, coal and minerals were all sold. Peter’s vision was to change the culture of a corporation from an internalised one, dominated by negotiations between upstream and downstream, to be more open to outside influences.

From the beginning, Peter made it quite clear to his colleagues that his role was to be that of a potential predator, to test whether they were getting as much value extraction as another owner. The approach did not always make him friends but the results were spectacular. From one of the weakest international oil giants, BP became one of the strongest with an earnings profile, a cash flow and a return on shareholders’ equity up among the best.

The programme involved some ruthless decisions. BP was among the first to undertake a drastic closure of refineries and other plant in the wake of the 1982/3 recession. Peter calculated that the first company to cut back would reap the advantages, be less likely to be blocked by governments and unions, and be able to buy supplies and services cheaply elsewhere. Profits from production successes in the North Sea and Alaska swelled reserves, while a rights issue in 1981 brought in £624 million and diluted the government’s shareholding to 31.5%. Peter received his knighthood in 1984.

In the US, BP’s subsidiary, Standard Oil of Ohio, had wasted billions of Alaskan revenues on poor exploration decisions and diversification into minerals. In 1986, Sir Peter took decisive action, sacking the US management team and installing as chief executive and chief financial officer two senior Britons, Bob Horton and John Browne. Horton went on to become chairman of BP, and Browne chief executive. Radical changes were put in motion including the disposal of many of Standard Oil’s non-oil investments. A year later, BP bought the 45% of Standard Oil’s shares that it did not own and at the end of July 1987 Standard Oil was merged with BP’s other US interests. BP America Inc. was the 13th largest industrial corporation in the USA, and the country’s largest oil producer.

In December 1987, BP grabbed a 15% share stake in Britoil in a dawn raid on the London stock market and then launched £2.5 billion offer for the whole of the company. Britoil was the successor to the British National Oil Company (BNOC) that was privatised in 1982. The two companies had joint interest in several North Sea oilfields and ownership of Britoil would add 40% to BP’s North Sea oil and gas reserves. BP‘s bid was successful and it was the first time that BP had bought oil reserves through the stock market, rather than developing them itself.

Sir Peter was convinced that BP could never be a top-rank international company with the British government as its biggest shareholder – foreign governments would always question its independence. In 1986, postponement of water privatisation left the UK government with a big hole in its budgeted finances and it decided to sell its BP shares. Sir Peter had hoped it would be done in three tranches but the sale was completed in one go. The sale was launched on 14 October 1987 to much razzmatazz with the offer price set at £3.30. However, within a week, the global stock market had suffered its Black Monday collapse and the market price fell below the offer price.

Sir Peter was concerned that with the price so low an unknown buyer could obtain a majority stake at a very low initial cost and asked for the issue to be withdrawn. This was denied and his fears proved prophetic as the Kuwait Investment Office (KIO) amassed 10% of BP’s equity by mid-November and continued buying. BP objected strongly and warned the British government that Kuwait might seek representation on its board and could soon be in a position to dictate BP’s North Sea oil production. The government referred the Kuwaiti issue to the Monopolies and Merger Commission which ruled that the holding operated against UK public interest and ordered the KIO to reduce its holding below 10%. Unable to find a buyer for the KIO’s shares, BP bought more than half of them in January 1989.

In his last letter to BP shareholders in February 1990, Sir Peter was able to report that the company had ended the 1980s with a record profit of more than £1.7 billion. Oil prices had recovered and demand was strong. ‘BP is now in a period of what could be termed aggressive consolidation,’ he wrote. ‘Our capital expenditure programme is focussed on opportunities in our mainstream businesses: exploration and production; refining and marketing, and chemicals. Thus we are concentrating on our traditional areas of strength.’

Summing up his time as chairman in an interview with Adrian Hamilton, deputy editor of The Observer and printed in Shield magazine (1990, no. 1), Sir Peter said: “Being chairman, I suppose, has suited my particular strengths, my bent for strategy. I’m really more of a general than a battalion commander.”

In his own review of Sir Peter, Adrian Hamilton wrote: ‘Oilmen have been traditionally explorers, traders or deal-makers. Sir Peter has been none of these things. What he has been is a professional manager who has addressed, with a rare logical intelligence, the problem of how to turn a large organisation brought up in one way to adapt to the problems of a quite different era.’

After leaving BP, Sir Peter took his analytical interest in strategy and structure, as chairman, first to Blue Circle and then to the Midland Bank. In 1994 he became chairman of the pharmaceutical company SmithKline Beecham and led it into its merger with Glaxo six years later.

Our thanks go to Ian Woods, bp archive manager, for providing the two photos of Sir Peter, together with the article from Shield magazine.